THINK TANK

Mutual Funds:

Balancing Risk and Opportunity

Rising MF investments are a vital part of India’s growing ‘financialisation’, but there are risks involved in the way the sector is shaping up

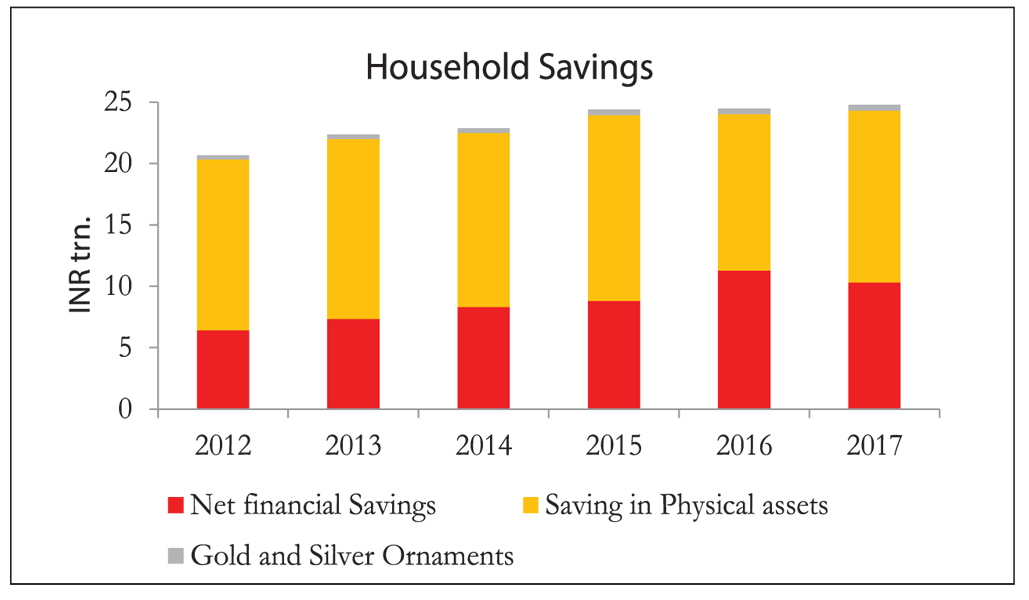

In recent months, IMA India has closely tracked the growing ‘financialisation’ of India. India’s natural progression towards this is on account of a younger population more aligned to financial savings, high market returns and a push in recent years by market players on financial literacy (In 2012, SEBI mandated 2 bps of the AUM (Assets Under Management) of each AMC to be allocated to investor education; AMFI (Association of Mutual Funds of India) is today one of India’s largest advertising accounts). A big fillip to this was the NDA government’s policy- and regulatory push towards greater formalisation – the creation of over 330 million Jan Dhan accounts, the growing use of DBT payments and the GST. Households today are investing a rising share of their savings in financial, as opposed to ‘real’ (gold and real estate) assets.

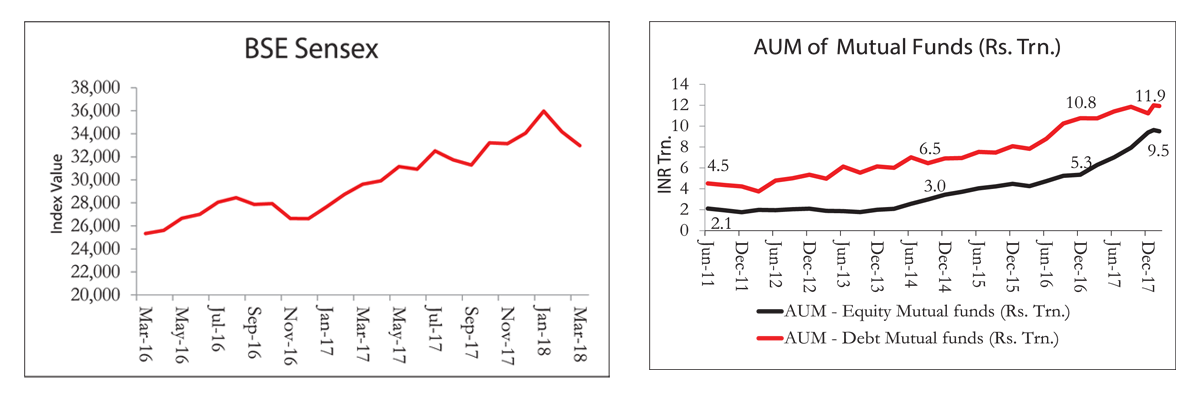

Mutual funds have ramped up their influence on the domestic equity market. From about 3.5 per cent of the BSE’s market capitalisation in March 2015, by December 2017, their share had gone up to about 6 per cent

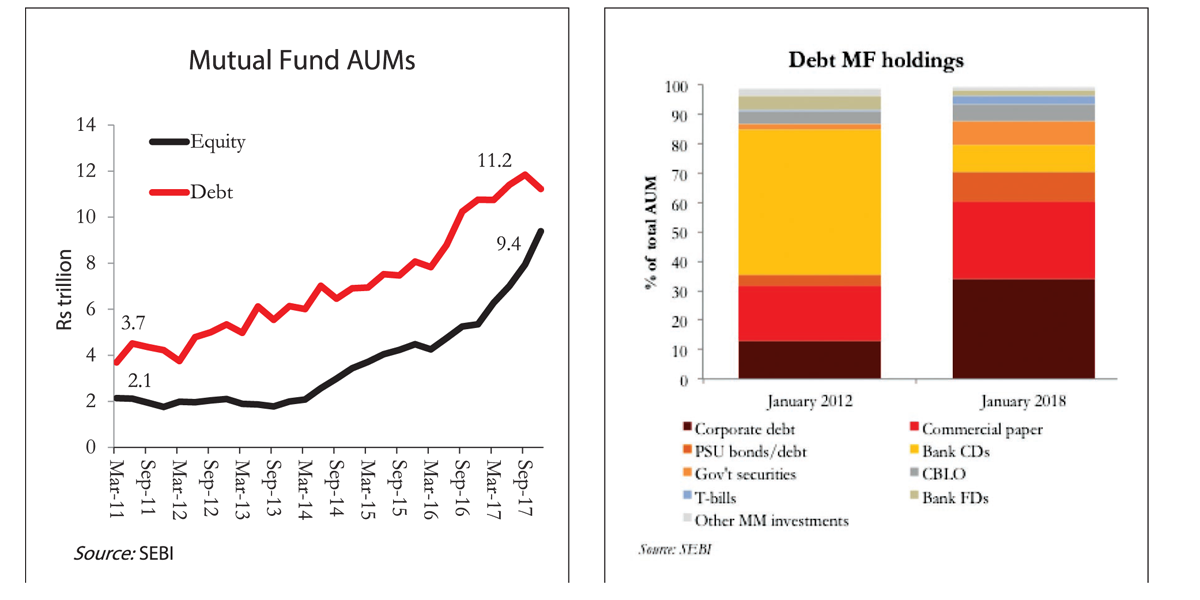

The most visible face of this change is a surge in mutual fund AUM, which grew at a compounded 21 per cent between March 2011 and December 2017 from Rs 9 trillion to a whopping Rs 21 trillion. Growth in mutual fund AUM between December 2016, just after demonetisation, and December 2017 stood at 30 per cent. Equity investments, mainly through the SIP route (monthly commitments have doubled in just the last two years) have hogged the limelight but there are equally important, if less dramatic, changes afoot on the debt-market side. For the most part, the direction of change – at both ends of the market – has been positive, though there are lurking risks to watch out for as this nascent trend starts to take root.

A STABILISING FORCE – AND A MORE INFLUENTIAL ONE

The mutual fund industry’s share of the domestic equity market has risen from about 3.5 per cent of the BSE’s market capitalisation in March 2015 to about 6 per cent by December 2017. Considering that company promoters currently hold about 47 per cent of all outstanding shares (by value), just over half (53 per cent) of shares are freely tradable. Effectively then, MFs now control over 10 per cent of the freely-tradable segment of the market. On the positive side, this has enabled domestic MFs to balance out volatile FII flows. When FIIs have sold on net, MFs have tended to buy, stabilising the market in the process. This is a far cry from even a few years ago, when the market – and the Rupee – would rise and dip sharply with foreign inflows and outflows.

DEBT MFS: TO THE FORE…

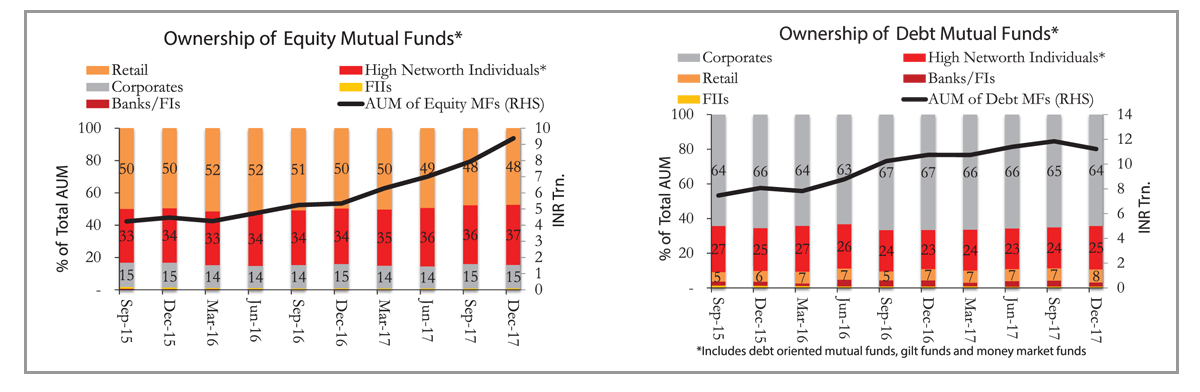

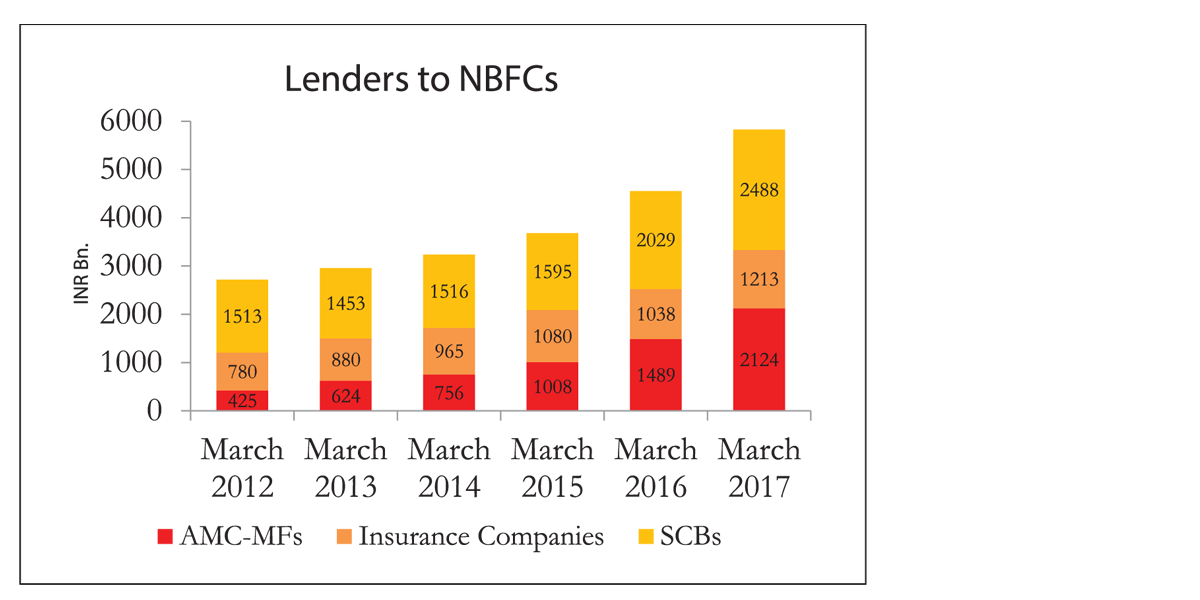

The more interesting part of the Indian MF story lies on the debt side. Weighed down by heavy NPAs, bank credit-growth to industry has been anaemic in recent years, but non-bank sources have picked up the slack. Strikingly, in 2016-17, banks made up much less than half (38.4 per cent) of all corporate borrowings, down from 56.3 per cent in 2011-12. Even more striking, debt MFs – whose AUM have tripled, to ~Rs 11.2 trillion since 2012 – now put about 34 per cent of their total assets into corporate debt, double what they did (17 per cent) in 2012, and a further 26 per cent in short-term commercial paper. At the same time, housing finance companies, commercial banks and especially NBFCs – where 18 per cent of all debt MF deployments now end up – are relying more and more on mutual funds. (On the other side of the equation, debt funds account for about 39 per cent of all NBFC liabilities, compared with just 16 per cent in 2012.) During this period, the ownership of debt MFs has remained broadly stable: corporates account for just under two-thirds (64 per cent), while HNIs and retail investors make up another one-third (33 per cent).

...for investments – and lending

Clearly, both businesses and individual investors are channelling significant – and fast-growing – amounts into debt funds, which tend to offer better post-tax returns than do bank deposits. At another level, MFs are rapidly displacing banks as a source of funding, not only for stand-alone corporates, but also for finance companies. Savings, in other words, are getting channelled through MFs back into the financial system, and are then being used to fund housing and other loans. The massive growth in personal loans that has occurred in recent years – supporting end-consumption in the process – has thus been enabled, at least in part, by the debt MF industry. This is more than welcome, because it means that savings are getting channelled more efficiently, into sectors where money is needed. It has also helped grease the wheels of finance – and also, ultimately, consumption and industry – which may otherwise have ground to a halt under the burden of NPAs.

WHAT LIES BENEATH

The impact on banks, and bank lending

There are however some unintended consequences of this huge inflow of funds into the financial system. Data suggests that higher-quality debt, particularly post-demonetisation, is migrating to mutual funds, leaving it to banks to compete for the remaining, riskier assets as yields for higher-rated (AA- or higher) debt fall (and rise for lower-rated issues). According to a recent RBI paper on the subject, there is now a very large ‘corridor’ between the risk-free (Repo/T-bill) rate and the SBI’s MCLR. India’s bigger, better-run companies and financial institutions can, and will, issue debt at rates that fall between these upper- and lower- boundaries, making bank borrowing less attractive. In itself, this is desirable because one of the main causes of today’s NPA crisis was an excess of large, long-maturity bank loans. (Clearly, the Indian debt market remains under-developed; most placements are private, and held to maturity, rather than being publicly listed and freely traded) This does, however, expose the riskier end of the debt market. Falling outside this rate-corridor, less secure companies will continue to knock on bankers’ doors. Banks, in turn, could be forced either to lower their lending standards, or to lend at ‘discounted’ rates (not fully reflecting their cost of funds) only to better businesses. This would necessarily mean deteriorating asset quality of bank portfolios, lower profitability, or both. A fresh squeeze on lending might result.

…minorly so for MFs themselves

Meanwhile, mutual funds also face risks of another sort: the rising concentration of NBFCs, housing finance firms and banks in their portfolios. Should NBFCs see a worsening of asset quality, or large, unexpected write-offs, debt MF investors could take a hit. There is a nascent, but please ratcheting-up of NBFC gross non-performing assets, from 3.3 per cent in March 2013 to 4.9 per cent in September 2017. The knock-on effect on corporate as well as retail investors could be significant, impacting economy-wide consumption and growth.

…and for the first time investor

Equally, India’s IPO market must mature faster. In the absence of enough new listings of adequate size and quality, mutual funds will be compelled, especially owing to their SIP commitments, to continue buying from the existing pool of shares. In time, this could drive already high valuations even more out of line with earnings than they currently are – raising the risk of a sharp correction that could destroy huge amounts of investor wealth. This is critical, particularly at this inflection point of the market.

Discussions with IMA’s Forum members from the sector suggest that a big part of the mutual fund component of India’s stock markets is driven by younger, first-time investors turning to financial markets on account of strong exhibited returns (17 per cent Sensex returns for FY17), greater financial literacy and a generational shift away from ‘productively dead’ (in the short/medium term) assets like gold and real assets. This search for more liquid and visible gains saw many investors enter the markets when they were already over-valued, thereby limiting the potential upside. In addition, whilst the cooling-off of markets in the last two months was almost expected, it was accelerated by FPI pull-out in light of changes in the US (USD 1.3 bn net FII outflows in February-March 2018) and by the decision on long term capital gains in the 2018 Union Budget. Industry players cite a concern, particularly as FPI activity is expected to remain muted with the US continuing its monetary tightening process, of spooking these players and therefore, the market.

All said, this deepening of India’s financial markets – guided, critically, by rising retail-investor participation – is to be welcomed. So long as all of these ‘not-insignificant’ risks that exist on both sides of the fence are recognised and mitigated, the longer-term impact on consumption, market stability and economic growth will be strongly positive.

IMA India for CFO Connect