THINK TANK

EBITDA Versus Free Cash Flow

Rajeev Akkineni explains how an excessive focus on EBITDA can mislead investors and lenders. A better approach is to read EBITDA in conjunction with free cash flow

In his 1989 annual letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffet had this to say about EBITDA:

‘When the leveraged buy-out craze began some years back, purchasers could borrow only on a reasonably sound basis, in which conservatively estimated FCF was adequate to cover both interest and modest reductions in debt. Later, as the adrenalin of deal-makers surged, businesses began to be purchased at prices so high that all FCF necessarily had to be allocated to payment of interest. That left nothing for pay down of debt.

“Cash is fact and accounting profit is opinion” – Scott Brayman in The Wall Street Journal (2002)

To induce lenders to finance silly transactions, borrowers introduced an abomination: EBITD . Borrowers ignored depreciation as an expense on the theory that it did not require current cash outlay. That’s nonsense. Such an attitude is clearly delusional. At 95% of American businesses, capital expenditures that over time roughly approximate depreciation are a necessity and are every bit as real an expense as labour or utility costs.

Even a high school dropout knows that to finance a car, he must have income that covers not only interest and operating expenses, but also realistically-calculated depreciation. He would be laughed out of the Bank if he started talking about EBITD.’

For the uninitiated, a leveraged buy-out (LBO) is where one company acquires another firm using significant debt (90% or more), by offering the assets of the acquiring as well as the acquired company as collateral security. The purpose of LBOs is to enable large acquisitions without having to commit a large amount of capital. Owing to their high debt-equity ratios, and because interest expenses exceed cash flows, many LBOs were classified as ‘junk bonds’. In the 1980s, they were the instrument of choice for corporate takeovers – and very often, they cause the acquired company to go bankrupt. It is ironic, then, that a company’s ‘success’ – measured by assets on its balance sheet – can be used against it as collateral by a hostile acquiring company.

In the United States, most dot-com companies sought to promote their stock by emphasising either EBITDA or pro-forma earnings in their financial reports, and explaining away the (often poor) ‘income’ number. Because EBITDA (and its variations) are not generally accepted under US GAAP, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires that firms registering securities with it to reconcile EBITDA with net income in order to avoid misleading investors.

Computing EBITDA

“Unless a company can generate cash to fund growth and pay dividends, its shares are essentially worthless” – A. Rappaport in The Wall Street Journal.

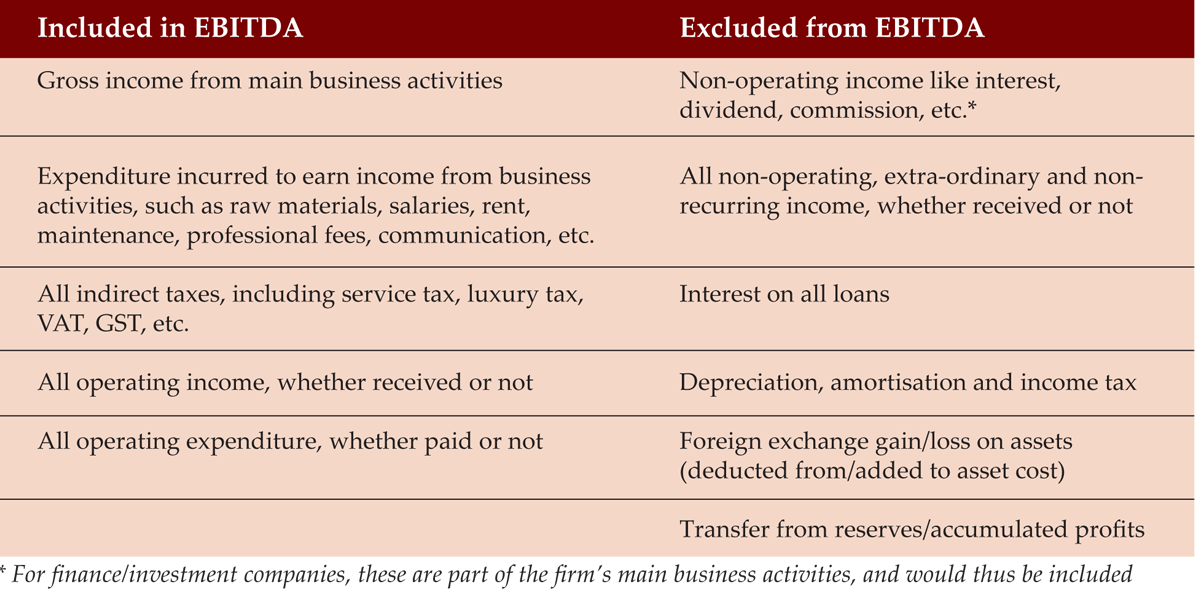

EBITDA measures the net operating profit/loss of a business. It includes operating income and expenditure, and excludes non-operating income and expenditure. The table below gives some examples of what is typically included or excluded in computing EBITDA.

Why is EBITDA used?

There are several reasons. First, EBITDA provides a benchmark against which the quality of company’s reported earnings can be assessed through reconciliation with operating cash flows. Second, it provides a measure of earnings that is not distorted by variations in the accounting treatment of depreciation and amortisation, the effects of financial leverage, and varying tax rates and treatments. This facilitates comparable company analysis on both a country-specific and a global basis. Third, for lenders, EBITDA can be used to assess the borrower’s debt-repaying capacity, based on the number of times EBITDA, or the percentage of EBITDA. For the principal portion, lenders typically look at EBITDA/debt, and for the interest portion, EBITDA/interest. Finally, investors use multiples of EBITDA for purposes of valuation.

Why EBITDA can sometimes be misleading

Although EBITDA has its uses, there are many situations where it falls short.

The exclusion of depreciation

Depreciation is a non-cash charge for a particular year, but it does entail cash outflow or debt availment when CAPEX is incurred. Depreciation and amortisation are similar to ‘prepaid expenses’. As with items like salary and rent, CAPEX is incurred to earn income from a business activity. Merely because it is paid in lump-sum does not mean that it can be excluded while assessing the profits of a business. Taking this analogy further, can any expenditure that is paid in advance – whether rent, insurance premiums, and so on – not be accounted as expenditure?

By not considering depreciation, EBITDA leaves its users blind to the company’s short-term and long-term asset replacement needs, which demand either cash or debt, or both. Crucially, when used exclusively to measure company health, EBITDA tends to show firms with asset-heavy balance sheets to be far healthier than they actually are.

Limited use

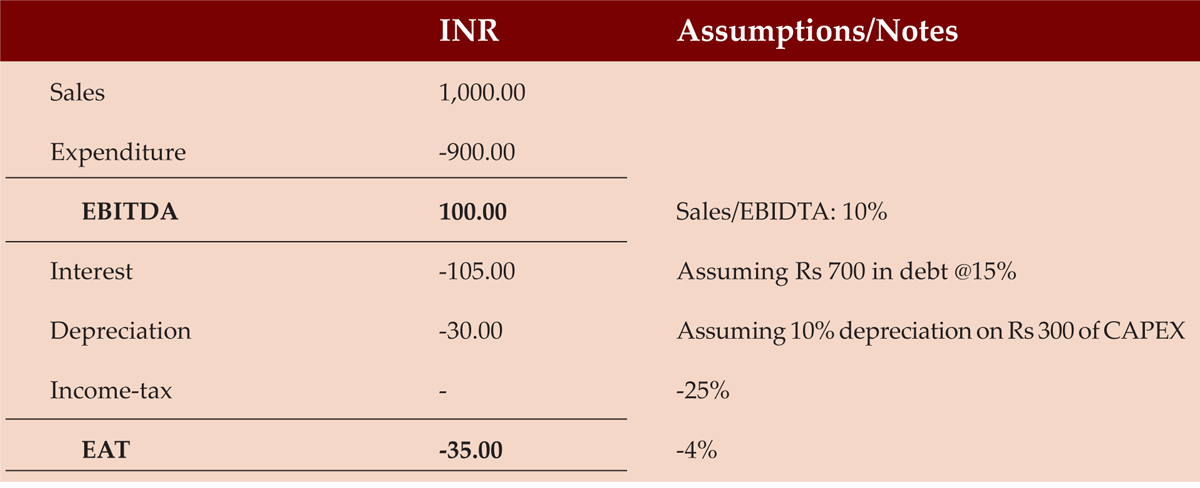

In addition to EBITDA, investors and lenders use DSCR (Debt-Service Coverage Ratio) to assess the debt-repaying and interest-paying capability of a business. Consider the example illustrated in the table below.

Here, even though EBITDA is positive, it is lower than the interest expense, implying that the business cannot fully repay its interest obligation, leave alone the principal amount. (Sales, in this scenario, equal 1.4x debt and 3.3x the value of fixed assets.) Also, if the annual CAPEX is assumed, on average, to be close to depreciation, the business will not have adequate cash for fresh CAPEX, at least until the loan is repaid.

EBITDA ignores working capital needs

In certain cases, a firm’s working capital needs will be much higher than its EBITDA. This might happen, for instance, if:

1. Several customers negotiate a much longer credit period, but are nevertheless accepted if they are strategic or referenceable customers, or if they place huge orders, etc.

2. Retailers need larger cash reserves to pile up inventories before the holiday season.

4. The cash required for paying creditors is brought forward from a previous period

In each of these cases, FCF would take into account the firm’s cash requirements.

EBITDA ignores poor cash positions

EBITDA is an earnings-based measure, and not a true measure of cash flow. Thus, even if its cash position is precarious, the company’s books might still reflect a high EBITDA. This may happen, for example, if uncollected sales increase EBITDA and EAT, but do not increase FCF or cash balance. Similarly, when inventory is purchased and paid for, but lies unsold, it does not decrease EBITDA or EAT, but it does decreases FCF.

Cases where EBITDA has been misused

In 2001, WorldCom Inc., then America’s second-biggest long-distance telecommunications company, had gross revenues of USD 39.2 billion. To avoid showing losses, it capitalised its lease payments of USD 3.8 billion, instead of accounting for them as revenue expenditure. It later admitted to wrong-doing, its CEO and CFO ended up behind bars, and in less than two years, its stock price fell from USD 64.2 to under a dollar.

With 36,000 employees, Parmalat, SPA was the largest multi-national dairy and food corporation in Italy, and the fourth-largest in Europe. During the 1990s, however, it committed various accounting frauds, aggregating to over USD 14 billion in value. Among other things, it inflated both its sales (through double-invoicing, and by raising product prices in its sales invoices), and its debts.

FCF: a better metric

In both of the cases above, EBITDA, and therefore EPS and net worth – but not FCF – were ramped up. (WorldCom even deliberately increased its cash flows from operating activities.) Both examples also highlight the need to carefully examine ‘cash flow from financing activities’, to understand where significant debt is being availed.

A key factor to consider is that EBITDA, EAT and RoCE include income even where it is not received in cash. On the flipside, they do not consider the cash that is required for CAPEX investments. Especially in capital-intensive industries such as automobiles and healthcare – where CAPEX is not only significant, but also recurring – this can be misleading. Here, FCF (defined as cash from operating expenses less CAPEX, whether replacement or growth-related) would be a better metric.

Note that, if CAPEX is unusually high or low during the period under review, it is not representative of the firm’s periodic/recurring CAPEX. In such cases, the average CAPEX incurred over the last 5-7 years (depending on the industry and the expected future needs) should be used. If additional working capital is envisaged on account of strategic and/or profitable-but-slow-paying customers, or because of external factors (a recession, tight liquidity in the market, etc.), it would be prudent to deduct it from FCF.

“Investment Bankers knew they could not (do business in) M&A anything at 150 times earnings, but at 20 times EBITDA, there were many fish to fry. And why ruin a beautiful earnings growth trend with those pesky (irritating) nuisances such as interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation?” – the Observer (a New York daily)

Although it is not recognised under GAAP, FCF reveals the net cash remaining in the business – which is something that both lenders and investors would (and should) be concerned with. Essentially, it is the ‘discretionary’ cash flow that is available for such purposes as: i. incremental debt reduction; ii. dividend pay-outs; or iii. share buybacks at the appropriate price. Spending FCF will not affect the ability to generate more FCF.

Recent trends in the use of FCF

Using FCF as a tool for analysis and valuation is not a recent phenomenon. Share-valuation, for instance, is always on the basis of the discounted value of future cash flows. However, accounting debacles such as the one at Enron in 2001 raised the interest in FCF dramatically.

Compensation

Increasingly, businesses are using cash flows or FCF to compute executive compensation. Consider, for example, the following announcements:

General Electric (2004): ‘125,000 of the performance share units will convert into shares of GE stock only if GE’s cash flow from operating activities has grown an average of 10% or more per year, during the 5-year period from 2003 through 2007.’

Bausch & Lomb (2004): ‘Operating unit performance is measured against targets established for sales, earnings, FCF, cost improvement initiatives, and strategic projects, tying incentive compensation to key shareholder return indicators.’

Nextel Communications (2003): ‘The compensation committee has adopted a long-term incentive plan intended to reward key management members for achieving specific performance goals relating to operating cash flow and net subscriber additions over a 2-year period commencing from 1-Jan-2002.’

Loan covenants

Loan covenants are express stipulations in loan agreements that increase the likelihood that the principal will be repaid, and that the interest on loans will be paid, as originally agreed. Two examples illustrate how FCF has been used by lenders in loan agreements:

IPC Acquisition (2002 Annual Report): ‘The Company (owing to loan agreement) made an excess FCF repayment of USD 30 million based upon 75% of the Company’s FCF for the period ended 30-Sep-2002.’

Motient Corporation: In 2003, the company was finding it difficult to service its debt, and had contemplated filing for bankruptcy protection in 2002. Lenders maintained a tight rein on the company by giving it a minimum monthly target FCF to generate. Although it failed to meet these monthly targets, it did stay on course on an annual/cumulative basis.

FCF: not without risk

Although superior to EBITDA, FCF does come with certain risks. In some cases, firms will exercise ‘creativity’ to report higher-than-justified FCFs – all with the aim of driving up executive compensation, securing better credit terms from lenders, and pushing up stock prices (especially ahead of an IPO, or prior to ESOPs being exercised). Unless accompanied by rising earnings, FCF can be fictitiously inflated by deferring payables to the next reporting period, classifying (when sold) ‘non-current investments’ as ‘current investments’, or receiving huge advances from customers (which, though, is generally a good thing).

Plainly, an excessive focus on EBITDA can be misleading – and had shareholders and lenders paid more attention to FCF, more frauds may have been detected earlier. However, the blame cannot be entirely attributed to EBITDA, because FCF is also prone to certain risks. At the end of the day, no measure or metric, when viewed singly, is immune to error or frauds. To be sustainable, cash flows require earnings support. A safer approach would be to examine EAT (not EBITDA) in conjunction with FCF.

Some Definitions

EBITA = Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortization, where

Earnings = Profit

Interest = Interest on all secured and unsecured loans (whether paid or payable)

Tax = Income tax (whether paid or payable)

Depreciation = Periodical write-off of tangible assets like Buildings, Plant & Equipment, Furniture, Vehicles, etc.

Amortization = Periodical write-off of intangible assets like Goodwill, patents, R&D expenses, etc.

CAPEX = Expenditure incurred to purchase fixed assets

EAT = Earnings After Tax

FCF = Cash from Operating activities less CAPEX

GAAP = Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

RoCE = Return on Capital Employed

Rajeev Akkineni is a Chartered Accountant and a Financial Consultant. He has been Chief Financial Officer in organisations across the IT, healthcare and infrastructure sectors.

Rajeev Akkineni is a Chartered Accountant and a Financial Consultant. He has been Chief Financial Officer in organisations across the IT, healthcare and infrastructure sectors.